Aftermath, and Memories of Dachau

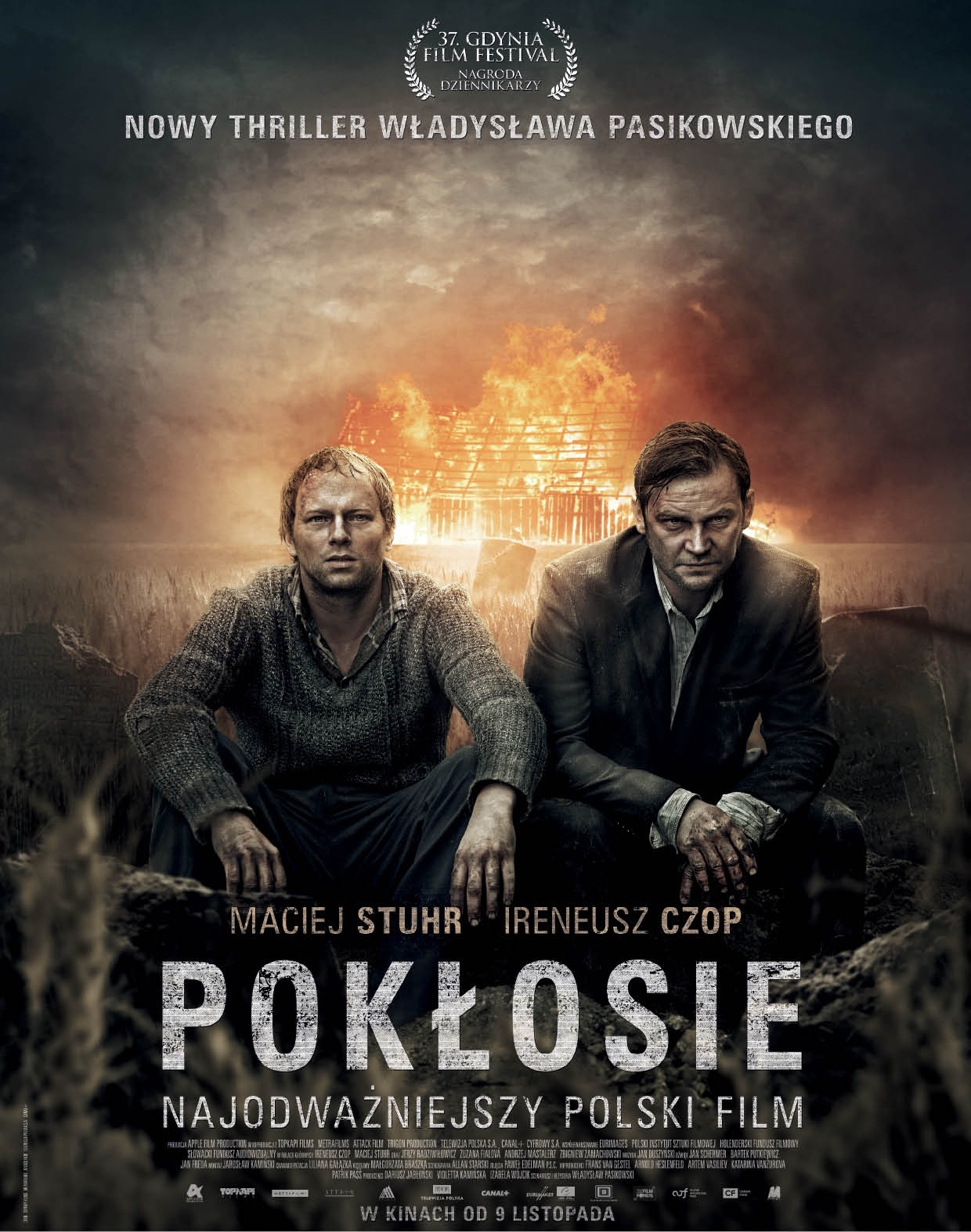

Buffalo's North Park Theatre ran one of the more challenging films in recent memory last week, Aftermath (Pokłosie) released in Poland in 2012 and starring Ireneusz Czop and Maciej Stuhr. The movie is down: and despite the otherwise brilliant theatre's unfortunate habit of running its best films for only one week - eliminating the possibility of any real word-of-mouth promotion or buzz - I still feel the way I felt when I left the theatre - namely, that I have to evangelize. That everyone I know has to see this film. So now I'm spreading the word; you can't find it on Netflix or Amazon Prime, but this is one worth searching for.[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8RJs8wAA2Y]Director Władysław Pasikowski's film is not a strictly "historical" drama, though critics (of which there were many) did try to pin it down as such, characterizing it as mendacious and manipulative. It did grow out of history, though, specifically historian Jan T. Gross' 2000 book Neighbors, the controversial account of the 1941 Jedwabne pogrom, in which poor Polish farmers murderd some 300 Jews - the entire Jewish population of their town - without the help or prompting of the Nazi occupiers, as was previously held.In Pasikowski's film, Czop's Franciszek Kalina, a Polish expatriate, returns to his hometown of Gurówka from Chicago after two decades to find his family house under siege, his brother on edge and hated by everyone, and the villagers silent.

Buffalo's North Park Theatre ran one of the more challenging films in recent memory last week, Aftermath (Pokłosie) released in Poland in 2012 and starring Ireneusz Czop and Maciej Stuhr. The movie is down: and despite the otherwise brilliant theatre's unfortunate habit of running its best films for only one week - eliminating the possibility of any real word-of-mouth promotion or buzz - I still feel the way I felt when I left the theatre - namely, that I have to evangelize. That everyone I know has to see this film. So now I'm spreading the word; you can't find it on Netflix or Amazon Prime, but this is one worth searching for.[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U8RJs8wAA2Y]Director Władysław Pasikowski's film is not a strictly "historical" drama, though critics (of which there were many) did try to pin it down as such, characterizing it as mendacious and manipulative. It did grow out of history, though, specifically historian Jan T. Gross' 2000 book Neighbors, the controversial account of the 1941 Jedwabne pogrom, in which poor Polish farmers murderd some 300 Jews - the entire Jewish population of their town - without the help or prompting of the Nazi occupiers, as was previously held.In Pasikowski's film, Czop's Franciszek Kalina, a Polish expatriate, returns to his hometown of Gurówka from Chicago after two decades to find his family house under siege, his brother on edge and hated by everyone, and the villagers silent. The brother, Józef Kalina, has been digging up and hoarding gravestones - Jewish gravestones used for everything from reinforcing roads to serving as flagstones at the Catholic parish church.The historical background, the tone, and the characters are distinctly Polish - the brothers, for example, fight up to their very last scene together, coming very close to fratricide, and there isn't a "reconciliation moment," as you'd find in a comparable American film - but Aftermath does have plenty of links to the American film tradition. The plot fits into "guilty town" tradition The cinematography, meanwhile, is reminiscent of Cormac McCarthy adaptations - with brutal, searing images, close shots, and natural lighting. I was most struck by the opposite character arcs, though: at first Franciszek doesn't sympathize with his brother's sudden compassion for the Jews; finally, crushed by the magnitude of the town's guilt and by his own unknowing complicity, Józef breaks and wants to cover it all up again, while Franciszek realizes that they have to see it through. Even then Franciszek is casually prejudiced against his "Chicago Jews" - but he's motivated by what was hidden half a century under his father's ancestral farm. Watching the brothers - always at odds - change, break, bend, and so beautifully cross arcs just before the film's shattering climax, I was reminded of the great moral dramas of the American masters, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, David Mamet. Pasikowski can stand among them, now.The Wednesday night screening at the North Park ended in silence, and some shocked, subdued sniffling. One cannot have a "reaction" to film - at least not right away. Most stayed in their seats until the credits - in Polish, mostly untranslated - had finished rolling, if only as an excuse to remain frozen, to put off standing and taking the long walk back to the real world.Once I was able to reflect on the film - once I was able to have something akin to a thought - my mind flew straight back to Dachau.I visited the concentration camp at Dachau in the summer of 2012, with my brothers and fellow travelers Steve Coffed and Matthias Spruch. There wasn't much talking between us. We perhaps two or three hours wandering, reading the many plaques and displays inside the administrative building, and staring across the blank brutalist flatness of the gravel-strewn plain still demarcated by the foundations of the barracks.

The brother, Józef Kalina, has been digging up and hoarding gravestones - Jewish gravestones used for everything from reinforcing roads to serving as flagstones at the Catholic parish church.The historical background, the tone, and the characters are distinctly Polish - the brothers, for example, fight up to their very last scene together, coming very close to fratricide, and there isn't a "reconciliation moment," as you'd find in a comparable American film - but Aftermath does have plenty of links to the American film tradition. The plot fits into "guilty town" tradition The cinematography, meanwhile, is reminiscent of Cormac McCarthy adaptations - with brutal, searing images, close shots, and natural lighting. I was most struck by the opposite character arcs, though: at first Franciszek doesn't sympathize with his brother's sudden compassion for the Jews; finally, crushed by the magnitude of the town's guilt and by his own unknowing complicity, Józef breaks and wants to cover it all up again, while Franciszek realizes that they have to see it through. Even then Franciszek is casually prejudiced against his "Chicago Jews" - but he's motivated by what was hidden half a century under his father's ancestral farm. Watching the brothers - always at odds - change, break, bend, and so beautifully cross arcs just before the film's shattering climax, I was reminded of the great moral dramas of the American masters, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, David Mamet. Pasikowski can stand among them, now.The Wednesday night screening at the North Park ended in silence, and some shocked, subdued sniffling. One cannot have a "reaction" to film - at least not right away. Most stayed in their seats until the credits - in Polish, mostly untranslated - had finished rolling, if only as an excuse to remain frozen, to put off standing and taking the long walk back to the real world.Once I was able to reflect on the film - once I was able to have something akin to a thought - my mind flew straight back to Dachau.I visited the concentration camp at Dachau in the summer of 2012, with my brothers and fellow travelers Steve Coffed and Matthias Spruch. There wasn't much talking between us. We perhaps two or three hours wandering, reading the many plaques and displays inside the administrative building, and staring across the blank brutalist flatness of the gravel-strewn plain still demarcated by the foundations of the barracks. The experience of visiting a concentration camp is stunning or even devastating because memory - the reason Dachau and places like it still stand - is at once so close and so ultimately inaccessible. We walk through the gas chambers, through the prisons, past the impossible bunk beds, under the gray sky down the long line of barracks; we pause at the chapel to hear the sisters sing; we descend into an underground memorial to look at some twisted sculpture made of metal from the old camp, look past that to light let in at a slit above. And in doing all this, for all the time that we're there and for some time after, we try very hard to access what actually happened. And we're moved; and some of us cry. But we can't really do it. The memory isn't ours.Aftermath ends with a group of Jewish travelers standing in the charred remains of the Kalinas' field, amid the heavy Hebrew headstones that Józef reclaimed. They pray, facing a bright new plaque on the final headstone - a memorial to the burning of hundreds of Jewish families in 1941. Like most of us who visit places like Dachau - or any memorial, really - the visitors in the movie's final scene cannot penetrate the marble or granite to find the flesh and blood - their own flesh and blood - the reason they've traveled across an ocean and half a continent to visit a fallow wheat field. But behind them stands Franciszek Kalina. He doesn't remember the burning of the Jews of Gurówka, but he quite literally dug up that past: he held their bones. And he is closer than almost anyone, at that point, to what actually happened. He remembers the blood spilled to make the memorial, to finally "remember," and he is the closest to remembering the flesh and blood there memorialized, the flesh burned more than half a century before.And here the entire movie is thrown back on itself, gaining a new and richer layer. Seeing Franciszek like that, observing from the edge, we, observing from a further edge, feel that we stand outside all of it. It's a Tralfamadorian effect: we see the Jews at the memorial, we see Franciszek and Józef fighting to expose the town's buried crime, and we can almost see the crime itself - a tale told earlier in a moving scene from Danuta Szaflarska. Thinking back on all this while faced with the memorial, we can't help but recall the countless memorials we've each visited, and in so doing see ourselves at our true distance from the "events," the murders or the tragedies, the flesh and the blood. And though we don't remember, we understand inarticulately what lies at the heart of all the concrete poured, all the marble and granite moved many miles from quarries to the sites of old crimes.Aftermath is a vital film; I hope it finds you.

The experience of visiting a concentration camp is stunning or even devastating because memory - the reason Dachau and places like it still stand - is at once so close and so ultimately inaccessible. We walk through the gas chambers, through the prisons, past the impossible bunk beds, under the gray sky down the long line of barracks; we pause at the chapel to hear the sisters sing; we descend into an underground memorial to look at some twisted sculpture made of metal from the old camp, look past that to light let in at a slit above. And in doing all this, for all the time that we're there and for some time after, we try very hard to access what actually happened. And we're moved; and some of us cry. But we can't really do it. The memory isn't ours.Aftermath ends with a group of Jewish travelers standing in the charred remains of the Kalinas' field, amid the heavy Hebrew headstones that Józef reclaimed. They pray, facing a bright new plaque on the final headstone - a memorial to the burning of hundreds of Jewish families in 1941. Like most of us who visit places like Dachau - or any memorial, really - the visitors in the movie's final scene cannot penetrate the marble or granite to find the flesh and blood - their own flesh and blood - the reason they've traveled across an ocean and half a continent to visit a fallow wheat field. But behind them stands Franciszek Kalina. He doesn't remember the burning of the Jews of Gurówka, but he quite literally dug up that past: he held their bones. And he is closer than almost anyone, at that point, to what actually happened. He remembers the blood spilled to make the memorial, to finally "remember," and he is the closest to remembering the flesh and blood there memorialized, the flesh burned more than half a century before.And here the entire movie is thrown back on itself, gaining a new and richer layer. Seeing Franciszek like that, observing from the edge, we, observing from a further edge, feel that we stand outside all of it. It's a Tralfamadorian effect: we see the Jews at the memorial, we see Franciszek and Józef fighting to expose the town's buried crime, and we can almost see the crime itself - a tale told earlier in a moving scene from Danuta Szaflarska. Thinking back on all this while faced with the memorial, we can't help but recall the countless memorials we've each visited, and in so doing see ourselves at our true distance from the "events," the murders or the tragedies, the flesh and the blood. And though we don't remember, we understand inarticulately what lies at the heart of all the concrete poured, all the marble and granite moved many miles from quarries to the sites of old crimes.Aftermath is a vital film; I hope it finds you.